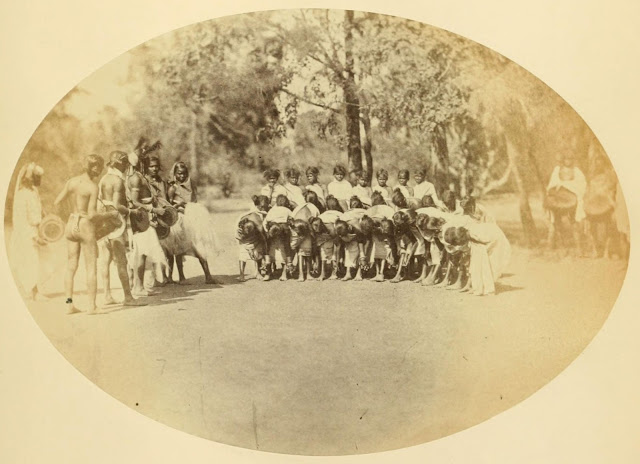

Cole National Dance

The country called Chota or Chootea Nagpore is the larger portion of an extensive plateau 2,000 feet above the level of the sea, on which are the sources of the Coel, the Soobunrekha, the Damodur, and other less known Indian rivers. The plateau is fenced in most places by a line of hills, some of which attain a height of upwards of 3,000 feet. The whole surface is undulating, sometimes gently, and sometimes abruptly, and the scenery is further diversified by interior ranges of hills, and the protrusion of vast rocks of granite, either in great globular masses, or in huge fragments piled up in most fantastic shapes.

The total area is estimated at 4,468 square miles, with a population of 645,359 souls, of whom about one-half are what are known to Europeans by the name of Coles.

The word Col or Kol is an epithet of opprobrium applied to these tribes by the Hindoos. It is a Sanscrit word, meaning pig or out-cast, and its further employment as a name for a people ought, as Major Dalton, the chief local authority, justly remarks, to be interdicted. It includes many tribes, but the people of Chota Nagpore, to whom it is generally applied, are either Moondahs or Oraons ; and though the two races are found in many parts of the country occupying the same villages, cultivating the same fields, celebrating together the same festivals, and enjoying the same amusements, they do not intermarry. The uniform tradition in Chota Nagpore is, that the Moondahs were the first settlers, and thus acquired certain proprietary rights in the soil, which they are most tenacious of to this day. In nearly every village are found descendants of these first settlers, who are called “Bhooyhars,” land-clearers, and their lands, called “ Bhooyharee,” are very lightly assessed at fixed rates, or, in some instances, held rent-free.

In ancient times the Coles acknowledged no Rajah, but the country was divided into groups of villages called “Purhas,” under chiefs who occasionally met and took counsel together as a confederacy. Traces of this old division are still found. The representative of the old chief of the “Purha” is still in some places amongst themselves styled Rajah, and a meeting of the “Purha" is called whenever it becomes necessary to take into consideration any breach of social observances by one of the tribe.

The Moondahs, the Coles of Singbhoom (called also the Lurka or fighting Coles, but properly the “Ho” tribe), the Sonthals, the Korewahs, and the Kherriahs, are all kindred tribes, speaking the same language, and having many customs in common. The Oraons, who also call themselves Coonkhur, are not of the same family; their language, which is quite different from the Moondah, shows that they are of common origin with the Hill-men of Rajmehal. No other tribe with which they can claim near affinity is known. According to their own tradition, they migrated ages ago from Goojerat, entered the Rhotas hills and Rewah, and when driven from thence, found themselves, after many wanderings, on the Chota Nagpore plateau, and being a peaceable and industrious race, they were well received by the Moondahs, and found no difficulty in obtaining from them permission to settle.

Since that period the two races appear to have lived harmoniously together, assimilated to each other in customs, joining together in amusements, sports, and ceremonies, so that to a casual observer they appear like one people ; but, as before stated, they never intermarry, and each race retains its physical peculiarities.

Physically, the Moondahs are the finer race of the two ; they are taller, fairer, better proportioned, and have more intellectual features. The Oraons are generally a dark-complexioned, short, thick-set race, with round, good-humoured faces of rather a lower type; but neither are wanting in intelligence. The Oraons are the more industrious and energetic ; and it is generally people of their tribe that, under the denomination Dhangur, are employed on great works in all parts of India and in the colonies. The Moondahs mostly love their ease and their lands too much to become voluntary wanderers.

The Coles are frequently spoken of as a wild Hill race living in a jungly country. In reality, they are not far, if at all, behind the agricultural classes of Lower Bengal in point of civilization ; their country is for the most part highly cultivated, and they generally live in villages sheltered by mango and tamarind groves of most venerable and picturesque appearance.

The Oraons and Moondahs dispose of their dead in the same manner. They bum the body near some stream or tank, collecting the ashes in an earthen vessel, which they bury. After a lapse of three years the vessel is taken up, and amidst a curious medley of singing and weeping, lamenting and dancing, re-buried under a large flat stone previously procured and placed in position alongside of those which mark the graves of the deceased’s forefathers in the village cemetery.

In marriages, the Moondahs preserve many ceremonies which the Oraons do not recognise ; some of these are singular. Preliminaries having been settled, the chief brings the price that is to be paid for the girl, which, in Chota Nagpore, varies from seven to ten rupees. The bride (always an adult girl), and the bridegroom, are seated amongst a circle of their friends, who sing whilst the bridesmaids rub them both with turmeric. This over, they are taken outside and wedded, not yet to each other, but to two trees; the bride to a muhoowa tree, the bridegroom to a mango. They are made to touch the tree with "Sindoor" (red powder), and then to clasp it in their arms. On returning to the house, they are placed standing face to face on a curry stone, under which is a plough yoke supported on sheaves of straw or grass. The bridegroom stands ungallantly treading on his bride’s toes, and in this position touches her forehead with “Sindoor.” She touches his forehead in the same manner. The bridesmaids then pour over the head of each a jar of water. This necessitates a change of raiment. They are taken into an inner apartment to effect this, and do not emerge till morning.

Next morning they go down to the river or to a tank with their companions, and parties of boys and girls form sides under the bride and bridegroom, and pelt each other with clods of earth. The bridegroom next takes a water vessel and conceals it in the stream ; this the bride must find ; then she conceals it for him to find. She then takes it up filled with water and places it on her head. She lifts her arm to support her pitcher, and the bridegroom, then standing behind her with his bow strung, and the hand that grasps it lightly resting on her shoulder, shoots an arrow between her arm and the pitcher. The girl walks on to where the arrow falls, and, with head erect, still supporting the pitcher, picks it up with her foot and restores it to her husband. What is meant by the battle of the clods and the “hide and seek” for the water vessel, is not apparent, but the meaning of the rest is plain. The bride shows that she can adroitly perform her domestic duties, and knows her duty to her husband, and in discharging an arrow to clear her path of an imaginary foe, the latter recognizes his duty to protect her.

In the Oraon marriages many of these symbolical ceremonies are omitted, and the important one of exchanging the “Sindoor” is differently performed.

Very few Coles indulge in the luxury of two wives at a time, but there appears to be no law against a plurality, if the man can afford to maintain more than one.

The Coles, whether of the Moondah or Oraon tribe, are passionately fond of dancing, and it is as much an accomplishment with them as it is with the civilized nations of Europe. They have a great variety of dances, and in each steps and figures are used of great intricacy, and performed with a neatness and precision only to be acquired by great practice. Children, once on their legs, immediately set to work at the dancing steps, and the result of this early training is that, however difficult the step and mazy the dance, the limbs of the girls moveas if they belonged to one body. The Coles have musical voices, and a great variety of simple melodies.

The dances are seen to greatest advantage at the great periodical festivals called “Jatras.” These are held at appointed places and seasons, and when the day comes, all take a holiday and proceed to the spot in their best array. The approach of the groups from the different villages, with their banners and drums, yaktails, waving horns, and cymbals sounding, marshalled into alternate ranks of boys and girls, all keeping perfect step and “dress”—boys and girls, with headdresses of feathers and with flowers in their hair, the numerous brass ornaments of the young men glittering in the sun—has a very pleasing effect.

In large villages where there are Oraons, or a mixture of Oraons and Moondahs, there is a building opening on the “arena” called a “Dhoomcooriah,” in which all the unmarried men and boys of the village are obliged to sleep. Anyone absenting himself and sleeping elsewhere in the village is fined. In this building the flags, musical instruments, and other “property” used at the festivals, are kept. They have a regular system of fagging in the “Dhoomcooriah.” The small boys have to shampoo the limbs of their luxurious masters, and obey all orders of the elders, who also systematically bully them, to make them, as is alleged, hardy. In some villages the unmarried girls have a house to themselves, an old woman being appointed, as a duenna, to look after them.

There is very little restriction on the social intercourse between the young men and the girls. If too close an intimacy be detected, the parties are brought before the “Purha” and fined, and if the usual arrangements can be effected, they are made to marry. If a girl is known to have gone astray with a “Dikko,” or stranger, she is turned out of the village, and will not be allowed to associate with her former companions, unless her parents can afford to pay a very heavy fine for her re-admission, and then the damsel must submit to have her head shaved, as a punishment to her and warning to others. (Information supplied by Major Dalton.)

From the Book "The people of India : a series of photographic illustrations, with descriptive letterpress, of the races and tribes of Hindustan"